This year will mark the 20th anniversary of 9/11. Less than two years after the turn of the millennium, one tragic September morning changed the shape of the world forever, dragging huge repercussions in international diplomacy, cultural relations, and civil liberties in its wake. For the last two decades “terrorism” has been talked about at all levels of society, from the Oval Office to household dinner tables.

Violent Islamist extremism has transformed Western collective consciousness, rejuvenating existing social divisions and empowering voices associated with “populist”, anti-immigration, and anti-multiculturalism sentiments. The media’s honeymoon with jihadist terror arguably peaked around 2017 when a new wave of attacks rekindled post-9/11 counterterrorism debates. Whether justified or not, it is no mistake to say that Western attention to jihadist terror has been one of the defining themes of the post-9/11 world.

While the public has almost exclusively concerned itself with this specific strand of terrorism, we should add that other forms of violent extremism, namely terrorism associated with the far-right and white supremacy, have also proliferated in the last decades. Far-right terror has, until recently at least, more or less managed to avoid the amount of spotlight reserved to violent attacks perpetrated by those aligned to more extreme strands of Islamism – often known as jihadists. A careful reading of the Quran will reveal that even the word “jihad” has been hijacked to denote violence when, in fact, the term is much broader than that and it even entails internal struggles with our, let’s say, “dark side”. Setting aside this controversy, the fact is: while terrorism has been often associated with more extreme strands of Islamism, individuals aligned with nativist, Islamophobic, and anti-Semitic views are becoming more and more violent. While lurking in the shadows of suburban home basements and the darkest corners of the web, the far-right has built enough of a track record to deserve our attention.

After two decades of complex socio-political developments, it is useful to look at the numbers and assess the frequency and scope of both Islamist and far-right extremist violence in the XXI Century. 9/11 is a helpful date when analysing general trends in terrorism even if it only refers to an Islamist terror attack specifically. This is because it represents a watershed in the way we think about terrorism in the West. In the wake of 9/11, the struggle against violent extremism went from being a top priority for national governments, to the purpose of states’ existence itself.

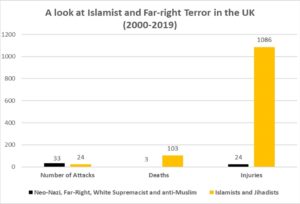

The Global Terrorism Database (GTD) allows us to survey the data on far-right and Islamist attacks in the UK from the year 2000 to 2019. The data refers to terrorist attacks perpetrated in the United Kingdom by Islamist and Jihadist groups on the one hand, and neo-Nazi, far-right, white supremacist and anti-Muslim extremists on the other. When using the shorthand “far-right” the article refers to all categories mentioned in the latter group.

Global Terrorism Database: The Numbers

The GTD reveals that, overall, far-right attacks have been more frequent than jihadist attacks, but far less deadly. The data suggests that attacks in the UK perpetrated by Al Qaeda, ISIS and other jihadi-inspired extremists where 24 in total since the year 2000, whereas attacks perpetrated by neo-Nazi, far-right, white supremacist and anti-Muslim extremists where 33. However, while casualties caused by jihadist attacks, as recorded by the GTD, where 103 fatalities and 1086 injuries, casualties caused by far-right groups only amounted to 3 fatalities and 24 injuries.

A significant trend which appears to be emerging is that far-right attacks are increasing in frequency and scope. 11 attacks (33% of all attacks since 2000) and a full 22 injuries out of 24 are concentrated in the years since 2017. This suggests that in the last 5 years far-right extremism has become more prominent than it was. Jihadist terrorism is somewhat more spread-out throughout the 20 years considered. However, in the UK, it appears to have spiked in the 2000s and in the years between 2015 and 2017, a period of three or four years when, many will remember, it seemed almost impossible to read the news without hearing about a new bomb, shooting or stabbing in some Western city. Since 2018 the UK has seen two attacks linked to jihadist groups.

Source: Global Terrorism Database

Double Standards

The data is indicative of the gross numbers involved in terrorism in the UK, but the thoughts of terrorism experts enable to paint a more complete picture of Islamist and far-right extremist violence.

In a 2020 paper, Professor of Law Kent Roach of the University of Toronto argues that Western counterterrorism mechanisms promote significant structural biases. These are evident in terror group proscription and conviction numbers, in the application of existing anti-immigration and anti-financing laws, and even in the likelihood of convicts accessing rehabilitation schemes. These biases systematically undermine the struggle against far-right extremist violence, while explaining the media’s and the public’s apparent disinterest in far-right terror. These biases, significantly, reflect authorities’ hesitance in designating far-right groups as terrorist at all, something which further explains negligence in dealing with far-right and white-supremacist extremist violence.

Why has it taken so long for authorities to label violent far-right attacks as terrorist?

According to Mr. Roach, there are several contributing factors which explain authorities’ reluctance in treating far-right attacks as terrorism.

Firstly, when dealing with far-right attacks, legal waters are often muddied by parallel charges relating to hate crime and mental illness. Moreover, as the data from the GTD confirms, far-right terrorism appears to operate on a much smaller scale than its Islamist counterpart. Far-right attacks appear to be done largely on the cheap, by single individuals or small groups, with few outside ties or communication, involving little or no travel. This makes far-right terrorists difficult to target with existing anti-financing and anti-travel laws.

The author also fears that implicit biases in our understanding of terrorism may be conducive to Western general inattention to the growing threat of far-right and white supremacist extremist violence. Since 9/11 the collective image of terrorism in Western countries has been one of Islamists in far away lands, “scheming to destroy our lifestyle and freedoms”. This has challenged a broader, more accurate, understanding of terrorism which includes its homegrown and non-Islamist varieties.

A 2015 study by Tahir Abbas of Leiden University and Imran Awan of Birmingham City University highlight that existing counterterrorism structures, which in essence reflect our discursive biases, promote the institutionalisation of islamophobia. This distorted understanding of extremist violence ultimately hinders the struggle against terrorism itself, as it leaves ample room for complacency on the part of the authorities and the public.

Is the situation improving?

The latest report by Hope not Hate suggests that authorities’ negligent attitude to far-right terror has started to change. The report applauds increased willingness by authorities to apply counter-terrorism legislation to the far-right, the recent involvement of MI5 against far-right terror, and the increased number of convictions. The report concludes that these developments point to law-enforcement taking far-right extremism more seriously.

It should be noted, however, that this newfound interest partly comes as an unavoidable consequence of an increased terroristic presence itself. According to the General Director of MI5, far-right terror, following the “perfect storm” of pandemic isolation and increased online presence, is now a threat second only to Islamist extremism. Increases in convictions still come with disproportionately lenient sentences.

Finally, the report finds that far-right terrorism is becoming younger, less tied to social networks, more online, and more internationalised.

By Matteo S. (University of Manchester – UK)