“We’re not just fighting an epidemic; we’re fighting an infodemic”

These were the words of Tedros Ghebreyesus, Director-General of the WHO in 2020 as the COVID-19 Pandemic proliferated across the globe alongside conspiracy theories. So, what are conspiracy theories (CTs) and why should we not just brush them aside as the rhetoric of men sporting tin foil hats?

Professor of Social Psychology, Karen Douglas defines ‘Conspiracy theories’ as “Attempts to explain the ultimate causes of significant social and political events and circumstances with claims of secret plots by two or more powerful actors”.

No wonder, then, that there has been an explosion of conspiratorial beliefs since the outbreak of the pandemic, with 3.2 million deaths across nearly 200 countries. A slow official response from many governments, often acting inconsistently and peppered with caveats, has forced populations to formulate their own explanations for the emotional trauma faced. Theories range from COVID-19 being an entirely bogus hoax, pre-planned and engineered by the Chinese government, to Bill Gates leading a mission to inject microchips, with some studies suggesting 28% of Americans believe Gates is indeed to blame.

Why Should We Take Note?

Despite often appearing delusional and far-fetched, conspiracy theories have some level of credence. Conspiracies can and do occur, as highlighted by the Watergate Scandal and the Iran‐Contra‐Affair. However, conspiracy theories require close observation due to their real-world implications. Pandemic-themed conspiracy theories, for instance, have motivated some believers to film themselves walking into hospitals and demanding to see recovering patients, whilst elsewhere, entire communities have rejected mainstream medicine to the point where once-eliminated diseases, such as the measles virus, are making a come-back.

Besides, many perpetrators of terrorist attacks are known to have been keen supporters of conspiracy theories, with Dillan Roof, for instance, killing nine African American churchgoers in 2015 after being radicalised by online forums, hoping to initiate a race war. Here, it can be noted that conspiracy theories are more prevalent at the political extremes. Why do some estimates point to ¾ of us believing in conspiracy theories then?

Social Media and Psychological Factors.

The rise of the internet has allowed conspiracy theories to gain traction and bounce around communities, questioning official versions of events and offering counter-narratives. Due to COVID lockdowns, more of us are spending time confined at home and online, feeling compelled to conduct our own research. This is where films such as ‘Plandemic: The Hidden Agenda Behind Covid-19’ fill a lacuna, in which a scientist, Judy Mikovits, who was later discredited for fraud and scientific misconduct, pedaled ideas that the virus is ‘activated’ by face masks.

By the time the video was eventually removed from various social media platforms, it had been viewed upwards of 8 million times, and received in excess of 150,000 shares. Meanwhile, celebrities have fanned the flames, with musicians Keri Hilson and M.I.A, alongside actor Woody Harrelson and boxer Amir Khan, using their social media influence to accuse the roll-out of 5G technology for the severity of the virus. Again, the real-world implications of these claims were felt, with 20 arson attacks on 5G sites in the same week of these posts. Moreover, politicians have exacerbated the issue, posting videos that falsely claim that hydroxychloroquine is an effective treatment for COVID-19, resulting in one man dying after ingesting a fish tank cleaning additive made with the same active ingredient as chloroquine.

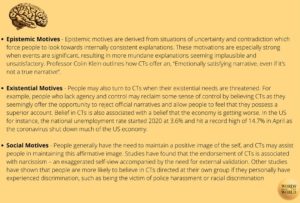

Researchers Au et al. showed that in one week in 2020, junk news channels, those websites that provide false information, received almost 30 million interactions, highlighting the popularity of conspiratorial belief and the power of an online presence. Such websites are often accompanied by emotional appeals to parents’ protective instincts, questioning them as to whether they would let their children fall ill due to a vaccine. Here, we consider the psychological dimensions of conspiracy theories, with Karen Douglas identifying three central traits:

What Should Be Done?

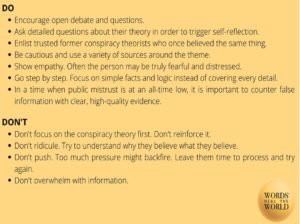

With past trauma and feelings of insecurity forcing a need to adopt alternative explanations, we clearly shouldn’t dismiss conspiracy theories as ridiculous falsities without justification, especially in light of the suffering perpetrated by COVID-19. To philosopher Bruno Latour, we need to instead gather evidence as opposed to debunking conspiracy theories immediately, with the information below, courtesy of the European Commission, outlining some ways of communicating with a believer of conspiracy theories:

Remember, use empathy and questions to stop the spread.

By Sebastian A. (University College London – UK)