Social Media

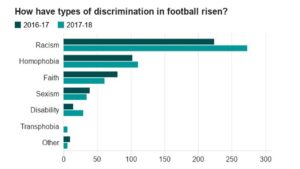

Despite racism in and around football matches being somewhat managed by English leagues, inclusion and diversity charity ‘Kick It Out’ released figures last year that highlighted how cases of racist abuse had in fact risen by 53 per cent between 2019 and 2020. Social media platforms are deemed central in enabling this hatred to grow, with direct messages and comments on players’ photos permitting those at the periphery of conversation to gain a central channel of communication, amassing an audience of millions.

Former Arsenal forward Thierry Henry, for instance, deleted his social media accounts following a spate of online racist abuse aimed at black footballers, testifying that social media companies were inadequately holding users accountable for their actions. Consequently, English football clubs and governing bodies commenced a three-day social media blackout in May of this year to protest both against the extent and lack of regulation targeted at online abuse. The appetite for more regulation on social media is growing in response to the depressingly long list of players who have suffered hateful online abuse, with many charitable organisations and key representatives, such as Prince William, president of the FA, deeming it essential that tech giants work harder to prevent users from being able to send explicitly racist terms and emojis.

Figure 1.0. The stark increase in racist discrimination in British football from 2016 to 2018. Homophobia, transphobia and hate against those with a disability all saw a notable increase too. Source: Kick It Out and BBC.

Social Darwinism

As Herman Ouseley, chair of ‘Kick It Out’ outlined to the UK’s Institute of Race Relations in November 2011, “The reality of racism in sport is the reality of racism in society”. The narratives we see in football are therefore a litmus test of wider race relations, mirroring writer and academic Paul Gilroy’s assertions that, “British nationalism cannot be purged of its racialized contents any more easily than a body can be purged of the skeleton that supports it”. As Professor John Valentine, author of, ‘Darwin’s Athletes: How Sport Has Damaged Black America and Preserved the Myth of Race’, has discovered, many of the racial stereotypes that persist in sport can be directly traced back to Social Darwinism. Whilst white people were deemed as holding superior intellectual and moral qualities within these concepts, black people were portrayed as lacking these attributes altogether. Instead, it was concluded that black folk had a greater need for physical strength and athletic capabilities to fill the void of intellect, making them ideal “natural” athletes.

Implications

Despite being entirely misplaced racist assumptions, these foundations continue to rupture the present, with one recent study by Dr Paul Ian Campbell revealing that black players are overwhelmingly praised for their perceived physical prowess and natural athleticism, in contrast to white players, commended for their intelligence and character. Moreover, these entrenched stereotypes help reinforce wider social myths in which black populations are depicted as hyperphysical and therefore suspected as posing a greater threat to society. In 2020, black people were nine times more likely to be stopped and searched by police in Britain compared to their white counterparts, with this number reaching as high as nineteen times greater for young black men in London, according to researchers at University College London’s Institute for Global City Policing. Equally, in schools, black children are five times more likely to be excluded for similar misbehaviour as white peers and are persistently predicted grades well below their intellectual talent.

Meanwhile, for black footballers, with the likes of Marcus Rashford, who was recently subjected to ‘at least 70’ abusive messages on social media following his team’s loss in the Europa League final, racist abuse has had innumerable implications. According to the British Association for Counselling and Psychotherapy (BACP), an increasing number of players are experiencing feelings of stress, depression, and anxiety as a direct result of racist abuse both on and off the pitch. The infographic below reveals the extent of this racism, with estimates of 54 per cent of fans globally having witnessed racist abuse while watching a game of football, with the lowest recorded percentage of 38 per cent in the Netherlands, remaining discouragingly noteworthy.

Figure 2.0. The proportion of football fans who have witnessed racist abuse while watching a game of football. Source: Kick It Out and Forza Football.

Thus, whilst it may be important to call attention to the need for more social media regulation by tech giants, greater societal recognition of the role of commentators and spectators of football who may unwittingly fall prey to treating black and white players differently is imminently required, with each of us needing to catch and nullify any casual racism in our surroundings. Racism acts like a virus, and if this past year has taught us anything, it’s better to catch the virus early before it spreads and becomes an everyday norm.

By Sebastian A. (University College London – UK)